As far back as 1793 the volunteers of New York City had sleds built to help respond through the snow filled streets. In that year, because of heavy snow the December before, sleds were built for Engine Companies 17, 18, and 19. (19 even was allowed 2 additional members to help pull the rig- due to their longer responses.)

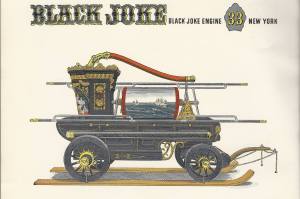

The cool picture of Black Joke Engine 33, shows their goose-neck pumper fitted with “runners” for hauling the machines through heavy snow. The other picture shows E-33 on the deck of a ship at the foot of Wall Street during the Great Fire of 1835. They were relaying water from a patch of open river to other pumpers on shore. Remember, all pumping then was done by hand!

* I have found no other mentions of the paid FDNY of using sleighs except the below photograph.

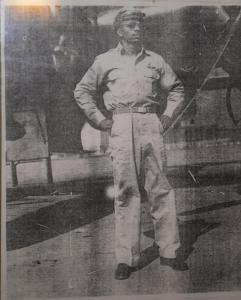

FDNY Lt. John Mulzac

Retired FDNY Lt. John Mulzac, a Tuskegee Airman who took to the skies in three wars, died this week.

He was 91.

Mulzac, a Brooklyn resident who was affectionately called Daddy John, was an original member of the elite Tuskegee Airmen, a group of 994 pilots who in World War II became the first African-American aviators in the history of the U.S. armed forces.

To his family, Mulzac, who died Sunday, was also a prankster and storyteller whose barrier-breaking history spoke for itself. But it was a tale the Bedford-Stuyvesant man enjoyed sharing nonetheless.

“They said that we could never fly airplanes, were not capable of flying airplanes,” Mulzac recounted to an auditorium of students at St. Saviour High School in Brooklyn in 2001. “But there were some people on our side.” The heroism shown by the Tuskegee Airmen is said to have influenced President Harry S. Truman’s decision to desegregate the military in 1948. The airmen were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2006, the highest honor bestowed by Congress.

“Despite the tough times of segregation he went through, he always felt this was the best country in the world,” said son Henry Mulzac, 60, a retired NYPD detective. “He was so grateful for what this country did for him and felt the service was worth it.”The pioneering pilot moved from manning flight controls to manning fire hoses when he became a smoke eater for the FDNY in 1947. He also started a family with his wife Beatrice, who pinned on his pilot wings at his graduation from the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1944. When the country called on Mulzac again, he left the firehouse to fly missions in the Korean and Vietnam wars as a reservist.

He retired from the Fire Department in 1967 as a lieutenant, then worked as a sky marshal and as a U.S. Customs inspector before retiring for good to concentrate on his role as the patriarch of a sprawling brood of eight children, 22 grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren, his family said.

Mulzac, who died Sunday, is survived by his wife, eight children, 22 grandchildren and eight greatgrandchildren.

“He was a man of integrity and he loved his children, and in his life he wanted to see them all get an education and strive for the best,” wife Beatrice Mulzac, 88, said Thursday at his wake.

That drive was an inspiration for the success of his family. His son Robert Mulzac followed in his father’s footsteps and is a retired FDNY lieutenant. Two of his grandkids, Channing Frye and Tobias Harris, play NBA ball for the Orlando Magic.

“What an inspiration. I knew I could do and be whatever because of him,” his daughter, Karen Mulzac-Frye said after Mulzac’s wake.“Now that he’s gone, I’ve got to work even harder.”

FDNY Rag Shop Fire 1957

The Unbelievable Story of Collyers Mansion

Salty Dog Apparel & Co.

John F. Mooney FDNY

From the Vault:

One Hundred Years Ago-

Another fireman chosen to be in the new Rescue Company was: John F. Mooney from Ladder Co. 4.

In 1912 Mooney made a daring rescue at 252 West 47th Street and was awarded the Wertheim and Department Medals.

On March 24, 1913 Ladder 4 arrived at the fire building, 320 West 58th Street, where a woman was clinging to a fourth floor window sill in the rear of the blazing building. The inner stairs were a sheet of flames so Mooney and Lt. Simpson hurried up the ladder to the roof.

Mooney laid flat on the roof and inched forward extending his head, then shoulders, then his upper body to the waist over the roof’s edge as the officer held his legs. Mooney leaned and stretched as far down as he could and grasped the woman by her hands. Using tremendous strength Mooney pulled her upwards. She and Mooney were now both dangling 60-feet above the ground. With an obstacle near the cornice Mooney extended himself even further to get into position to muscle her up and over the piece of iron work.

With one last effort the woman was raised up and over the ironwork and onto the roof.

This was the fourth time Mooney had been placed on the Roll of Merit.

The following year found Mooney on the steps of City Hall again. This time Mayor Mitchel was pinning the James Gordon Bennett and Department Medals on Mooney’s chest, for the best rescue of the year.

As the mayor pinned the two new medals on him he remarked, “You haven’t room for many more!”

He was an obvious choice for Rescue Company 1.

FDNY Rescue 1 Created

From the Vault:

One Hundred Years Ago Today-

After the tragic subway fire on January 6, 1915. FDNY Chief Kenlon and the commissioner put their plans for the creation of a new company- a rescue company, on the fast track. Kenlon chose a young captain, John J. McElligott of Ladder 1 to be the first commander. His lieutenant would be Edwin Hotchkiss of Ladder 21, who’d been cited for bravery and leadership at the recent subway fire. McElligott and Kenlon then hand-picked the remaining eight firemen (from hundreds of volunteers) who would become the first rescue men.

The applicants were checked out physically and evaluated for their skills. Being a proven fireman was of course the first critical criteria. Members who also had experience as mechanics, engineers, electricians, iron workers and riggers etc., were given preference. A tough physical and medical exam was given due to the severe work the new company was expected to encounter.

The new men were chosen, announced to the department on Special Order #10 and reported for the beginning of their specialized training. A new era in the fire service was beginning!

Next- the first rescue men. Paul Hashagen-author

Chief John J. Pritchard FDNY

Chief John J. Pritchard

“If you’re ever trapped in a fire, he’s the one you want coming for you.”

Standing all of five foot five and weighing in at a little over a hundred and fifty pounds, John J. Pritchard joined the Department in 1970 and quickly joined up with Rescue 2, an elite unit of the FDNY that specialized in showing up first to the scene, pulling people out of burning buildings while the structure collapsed around them, and then getting the hell out of there before they were crushed to death by flaming cinderblocks or asphyxiated from an insane amount of smoke inhalation.

Pritchard’s first documented experience putting himself at “extreme personal risk” for the sake of being totally fucking awesome came in 1975, when Rescue 2 responded to a three-story building that, by the time they got there, had already been lit up like a Kuwaiti oil field fire. With the first two floors completely engulfed in raging, rapidly-growing flames and a developmentally-disabled boy allegedly trapped up on the top floor, Pritchard didn’t even wait for orders before he sprung into action like a boss. He grabbed a ladder, threw it up against the side of the building, and sprinted to the top, smashing out a window and entering the building. The window was just a little too small to accommodate the oxygen tank he had strapped to his back, so naturally Pritchard did the completely batshit insane thing, took off his O2 tank, and climbed into the smoke-filled burning building without any supplemental oxygen.

Crawling around on the floor in an effort to avoid being immediately killed by the massive obscene amounts of black smoke that blackened the entire interior of the building, Pritchard made his way through the boy’s apartment, desperately trying to find him before it was too late. When he couldn’t find the boy in the apartment, he went out the front door into the hall, where he found the kid laying at the top of the apartment building stairwell, his clothes on fire. Pritchard smothered the flames, grabbed onto the kid, and prepared to head back, but the second he turned around the bullshit front door of the apartment closed and locked him out. Unable to breathe, with flames catching his uniform on fire and part of the ceiling coming down on top of him, Firefighter Jack Pritchard did the only logical thing that came into his mind in the heat of the moment.

He grabbed the kid, held him tight, and leapt over the banister rail towards the second floor.

Pritchard hit the ground hard, crashing into the second floor, where a hose team shot him with some water and evacuated both Pritchard and the boy to ambulances. He’d sustain second-degree burns on large swaths of his body, but it would take a hell of a lot more than that to keep Jack Effin’ Pritchard down.

Pritchard’s next major battle with flesh-melting heat came on August 2nd, 1978, when he was there for one of the most tragic days in FDNY history. It was early in the morning when a huge fire had broken out at Waldbaum’s Supermarket in Brooklyn, trapping several shoppers and construction workers inside. Fire teams had gone in to get those people out, but they’d run into trouble – a lot of it.

Jack Pritchard’s shift had ended a half-hour ago, but it’s not like that was going to stop this guy from hauling ass mask-first into a raging inferno to save his firefighter brothers. Rolling up to the front of the market while firemen swarmed along the rooftop hosing down the out-of-control blaze, Pritchard immediately threw on his fireproof coat and sprinted into the store, seemingly completely oblivious to the smoke and fire swirling around him. Running through the halls of the supermarket without a mask, oxygen tank, or hose line, Pritchard found one of the trapped firemen inside, pulled him out to safety, and then turned back in horror as the roof of the market collapsed, dropping a dozen firefighters down into the blaze. Pritchard sprung into action, rushing back into the store looking for trapped men. On three separate occasions he rushed into the market, ignoring massive burns all down his arms and chest, digging men out from under the rubble with his bare hands, dragging them to safety, then running back into the burning store. When the structure finally collapsed on itself, six firefighters were still inside. It was one of the deadliest days in FDNY history, though if it wasn’t for Pritchard that number would have been even higher. For his actions saving the lives of four firefighters at extreme personal risk to himself, Jack was awarded the James Gordon Bennett Medal, the highest award for individual bravery offered by the City of New York.

For the next 20+ years, Jack Pritchard fought pretty much every major fire in Brooklyn, putting out so many blazes that he’d actually developed effective new tactics for putting out fires in neighborhoods and apartment buildings. He prided himself on being the first man to every fire in the city, a point he drove home one cold winter night when he tried to drive his fire truck over the Rescue 1 team when they’d beaten him to a blaze – Rescue 1’s commanding officer only managed to avoid a make-out session with the Rescue 2 fire truck grill by diving head-first into a snow drift as Pritchard screamed by at full speed. A brash, ball-busting prankster who swore with the best of them and never backed down from a fight, Jack was also famous for breaking into his co-workers’ cars, stealing any food he could find, and then setting it out in the Firehouse kitchen so the entire team to could eat it. He never backed down from a fight, never took sick time, once had two ribs broken in a fist fight with his commanding officer, and routinely preached that there was nothing a firefighter could encounter that couldn’t be solved with two Asprin and a healthy amount of burn cream (they say that his entire upper body is covered in scar tissue because despite his many visits he never stayed in the hospital long enough for his wounds to heal completely).

Pritchard eventually proved himself such a hardcore little bastard that he was promoted to captain, transferred out of Rescue 2, and given his own command – Engine 255 on Rogers Avenue, Brooklyn, a unit that was better known as Captain Jack’s Jolly Rogers.

Captain Jack drilled the Rogers into one of the most efficient Engines in the city, demanding nothing less from his men than for them to have the fastest response times in the five boroughs. Of course, it’s not like Pritchard let his new promotion get in the way of running into burning buildings at the head of his men, either – when he responded to one house fire in 1992 he saw a badly-injured fireman being dragged out of there after failing to rescue the resident trapped inside, so Captain Jack, commander of Engine 255, just threw on his mask, ran in there, crawled through the burning house, carried the 70 year-old occupant out of there, and then spent the next two months running his unit from the burn ward.

Pritchard’s most famous action took place in July of 1998, when the Jolly Rogers were called to a massive fire in a six-story apartment building in the heart of Brooklyn. Arriving on the scene in under three minutes, when Jack leapt out of the fire truck cab he was immediately met by a woman screaming that her baby was trapped up on the fourth floor in a smoke-filled room that was also on fire.

Captain Jack didn’t hesitate. He told his men to get to work, then immediately ran up the stairs without bothering to grab a hose or a mask or an oxygen tank. He charged up to the fourth floor, and saw smoke pouring out from under the door of the apartment. Unable to smash through the locked door, and with time running out, Pritchard suddenly noticed that the woman’s keys were still in the lock on the door, so he took his bulky gloves off, turned the key, opened the door, and was almost knocked unconscious by a backdraft fireball exploding in his face.

But not even a fucking flamethrower to the face was going to keep this madman from saving the baby inside this place, and Jack immediately dropped down and began crawling through the black smoke towards the sound of the crying child. He made his way to the nursery, where he found the baby laying in a plastic playpen. The flames and smoke were so intense in the room that there was no way for him to pull the kid out of there without catching it on fire, so, even though he wasn’t wearing his gloves, he fucking didn’t the most insane shit ever and grabbed the melting plastic playpen with his bare hand and began dragging it out of the room. Burning the shit out of his hand every step of the way, and sucking down unhealthy amounts of carbon monoxide, Pritchard dragged the playpen through the apartment, calling out to his men to meet him at the door. With the playpen (and his hand) melting under the insane heat, Pritchard toughed it out, pulling the kid to safety and getting the baby out of there alive. For his actions he became only the second New York firefighter to receive the Bennett medal twice, and the first one to ever receive three Class One medals for “extreme personal risk” (he also has five Class Two and Class Three medals, but those are only for “great personal risk” and “unusual personal risk”, so no bigs or anything).

Jack Pritchard retired from the force with the rank of Battalion Chief. In 1999, when the 29-year veteran was receiving a prestigious medal for his service to the city, he didn’t give a big acceptance speech. He just said, “It’s a real honor to be a firefighter,” and walked back to his seat.

–thanks to Badass of the week.com

December 1960 Plane Crash

December 16, 1960-

At 10:34, on a foggy morning, two planes collided over NYC. One plane crashed at Miller Field in Staten Island. The second plane, struggled to stay aloft only to crash into one of the most densely populated neighborhoods in the city: Park Slope in Brooklyn. A wing clipped an apartment house as the plane drove into the street and a row of buildings at Sterling Place and Seventh Avenue. An elderly man startled by the crash, pulled the fire alarm box sending Engines 269, 280 & 219 along with Ladders 105 & 132 to Box 1231. The first due units arrived quickly to find 11 buildings in flames. Within minutes Battalion 48 had transmitted a 2nd & 3rd alarms. Lt. Bush of L-105 split his men and tried to cover the flaming fuselage of the plane and a blazing apartment building. As the officer and his team crawled into the burning building, Firemen Rogan & Dailey entered the blazing plane armed with only extinguishers. As Dailey held back the flames, Rogan cut two people from their seats and pulled them from the blazing wreckage. Amazingly the passengers were still alive.

Inside the apartment, heavy fire was filling the first and fifth floors as jet fuel fed flames burned up the outside and in through broken windows and gaps in the damaged structure. Fireman Browne found an elderly woman and together with Lt. Bush carried her to safety. They then found and removed an injured man just as the flaming building collapsed. Within ten minutes of the initial alarm, a 2nd, 3rd, and 4th alarms and special calls for Rescue 1 & 4 had been transmitted. The plane’s fuselage crashed into the Pillar of Fire Church which was completely destroyed by the resulting fire and explosions. Engine companies stretched lines and began battling the row of buildings set ablaze by flaming jet fuel.

The neighborhood was now in a complete panic. Mothers and their children fled from their homes onto the snowy streets. Others opened their doors to a wall of flames and had to escape through the rear. Rumors a school with 1500 students inside had been hit, only increased the drama. (Luckily the school was okay).

Despite the intense heat, and tottering walls, Rescue, Squad and Laddermen moved into the blazing areas covered by attack lines. Team after team advanced across the shattered debris and into the raging fires. In all 38 lines were stretched and operated. Thirty one engines, six ladder companies, three rescue companies, and four special units operated at this fire.

When the smoke finally cleared, the toll was devastating: 84 passengers on the Brooklyn plane were killed. Six people on the ground were killed, fifteen civilians and seventeen firemen were injured. In Staten Island all 44 people on the plane had been killed.

In Brooklyn, 200 off-duty firemen responded and worked at the scene. The firefighting and recovery efforts at this, the worst commercial airline crash (at that time), would go on for several days. For the next several days members of the FDNY combed the wreckage of the crashed airliner, and searched the shattered neighborhood buildings. Pockets of fire were extinguished as the devastation left behind became evident. The six people killed on the ground were: an elderly church caretaker, a sanitation worker shoveling snow, two men selling Christmas trees on the sidewalk, a butcher in his shop and a man walking his dog.

A total of 134 people had lost their lives.

For their heroic rescues upon arrival, Lt. Bush, Firemen Browne, Dailey and Rogan of Ladder 105 were later awarded medals. John Rogan was also treated at the hospital for second degree burns.

Paul Hashagen

The Equitable Building Fire

January 9, 1912 . Five alarms and a Borough Call. Numerous heroic rescues, millions of dollars in damage and six lives lost, including Battalion Chief Walsh. The square block, interconnected composite structure (actually made up of several buildings) proved to be one of the most difficult and dangerous fires the FDNY has ever faced. More of the “chilling” photos to come. Brrrrr!